Reading: Capital I, ch. 2-3; Limits to Capital (Harvey), pp. 1-20; Critique of Political Economy, ch. 2

In chapter 3, in his extended discussion of the circulation of money and commodities, Marx explains the dialectical movement of this process as follows:

“Commodities first enter into the process of exchange ungilded and unsweetened, retaining their original home-grown shape. Exchange, however, produces a differentiation of the commodity into two elements, commodity and money, an external opposition which expresses the opposition between use-value and value which is inherent in it. In this opposition, commodities as use-values confront money as exchange-value. On the other hand, both sides of this opposition are commodities, hence themselves unities of use-value and value. But this unity of differences is expressed at two opposite poles, and at each pole in an opposite way. This is the alternating relation between the two poles: the commodity is in reality a use-value; its existence as a value appears only ideally, in its price, through which it is related to the real embodiment of its value, the gold which confronts it as its opposite. Inversely, the material of gold ranks only as the materialization of value, as money. It is therefore in reality exchange-value. Its use-value appears only ideally in the series of expressions of relative value within which it confronts all the other commodities as the totality of real embodiments of its utility. These antagonistic forms of the commodities are the real forms of motion of the process of exchange.” (199)

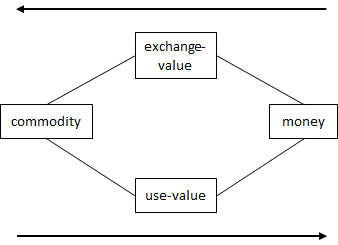

In the spirit of Harvey’s dialectical diagrams, I came up with one of my own here based on the above quotation:

The diagram expresses the confrontation of money with a commodity in the market. We see here a blending of forms. Conventional wisdom has it that a commodity and the money used to buy it are separate objects. But when understood dialectically, they proceed from their unitary forms to become fluid forms that are metabolized in the process of exchange, where they form a dynamic, interdependent process that then crystallizes once again when the exchange has been completed.

On the one hand, the commodity has both a use-value—in that it will be consumed by its buyer—and an exchange-value—in that it embodies a certain amount of socially necessary labor. On the other hand, the money has exchange-value—in that it embodies socially necessary labor (as does any commodity)—and use-value—which describes its function as universal equivalent. So the commodity, as it appears on the left-hand side, is “ungilded and unsweetened,” raw if you will as a use-value only, with its exchange-value hidden. The money is also raw in its own way because it is materialized exchange-value and its use-value is hidden. But their exchange on the market metabolizes them whereby they split into their use-values and exchange-values so that they can pass through the exchange process. This splitting is what forms the bond between them. As they move through the process in either direction, they are then re-formed on the other side as solid wholes. The money re-forms as the commodity and the commodity as money.

He continues: “To say that these mutually independent and antithetical processes form an internal unity is to say also that their internal unity moves forward through external antitheses. These two processes lack internal independence because they complement each other. Hence if the assertion of their external independence proceeds to a certain critical point, their unity violently makes itself felt by producing—a crisis.” (209)

Here Marx refers to the way in which money serves as the means to unify the process of exchange, which is split up in a capitalist market. Instead of directly exchanging one product for another, as in a barter economy (commodity—commodity), money separates it into two different steps (commodity—money—commodity). This allows for the realization of the commodities produced as capitalism establishes dominance over all economic relations. The implication then, is that if the interdependence of the process is broken, a crisis is created because value cannot be realized.

I am reminded of the current Coronavirus economic crisis in which the economies of several countries and regions have been shut down. As people have withdrawn physically from marketplaces (retail corridors, restaurants, etc.) commodity production has faced a crisis of realization. So the physical assertion of “external independence” by people breaks these bonds of commodity exchange as well.

On a slightly different topic Marx creates a distinction between commodities and money. He states the following: “Every commodity, when it first steps into circulation and undergoes its first change of form, does so only to fall out of circulation once more and be replaced again and again by fresh commodities. Money, on the contrary, as the medium of circulation, haunts the sphere of circulation and constantly moves around within it.” (212-3)

If money is just a commodity that has been elevated to the universal equivalent, can we not also say that there are other objects that perhaps serve as money, at least transiently, insofar as they are not withdrawn from circulation once purchased, but continue to circulate as value equivalents? For example, during a housing boom, houses, which are normally consumed as use-values to live in, are flipped to gain a profit from a rise in price. So money can be augmented by exchanging it for a different commodity that serves as mere exchange value. Perhaps this is the same with antiques and artwork.