Reading: Capital II, ch. 7-11

Part II, The Turnover of Capital, begins with a description of fixed and fluid capital. These are the two forms of capital found in productive capital. To review, productive capital is one of the three forms capital takes as it moves through the economy. Productive capital is that capital found in the production process where value is created. Money capital and commodity capital are solely found in the circulation process.

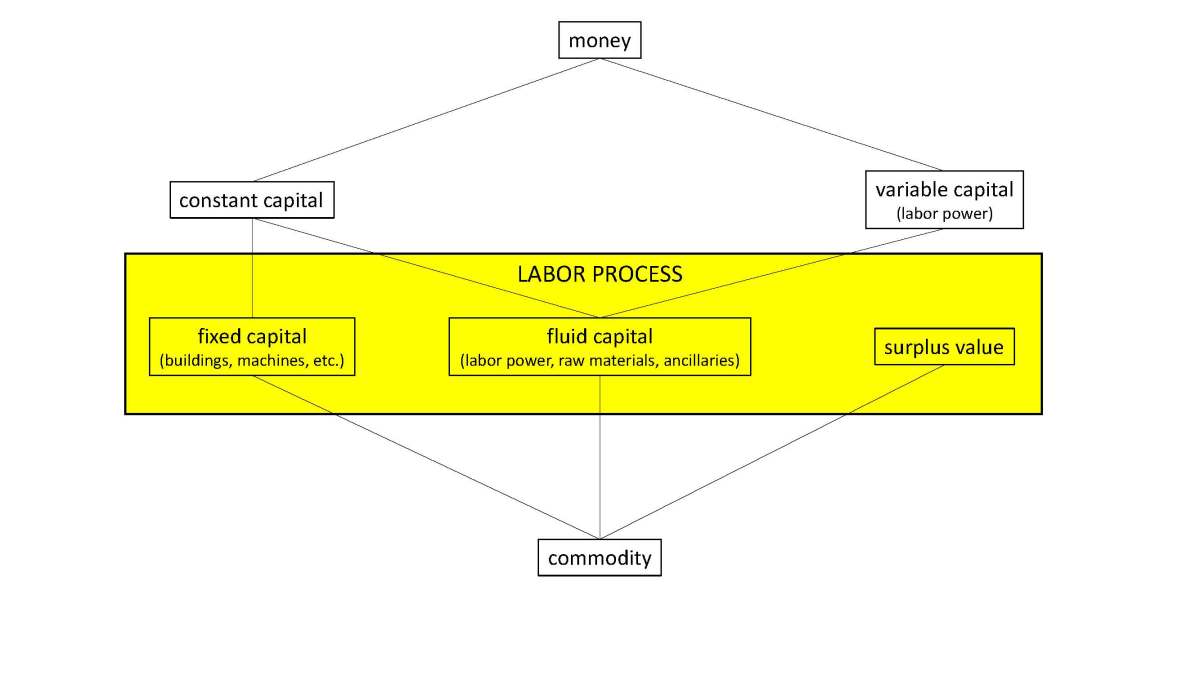

As described in chapter 1, productive capital consists of the means of production (constant capital) and labor power (variable capital). These are purchased on the market by the capitalist and consumed in the production process. The means of production transfer their value to the product, but labor power, when it is consumed, not only transfers its value to the product but creates new value, i.e. surplus-value.

However, there is a further distinction Marx is making that bridges the fundamental distinction between constant and variable capital—that distinction is defined by the turnover time of the capital employed in production. Capital that takes longer to turn over, i.e. longer to get used up before it needs to be replenished, is defined as fixed capital. Capital that is used up immediately and needs to be replenished on a regular basis is fluid or circulating capital. (I find the term “circulating capital” confusing because Marx applies the term to a different concept in refuting Smith and Ricardo.)

Fixed capital consists of items such as factory buildings and means of labor, e.g. machines, which after being purchased slowly degrade over the course of years. While the final product does not materially embody these fixed elements, it embodies their value, as a portion of that value is added to the products gradually over time as they depreciate.

Fluid capital consists of labor power, raw materials and ancillaries such as gas and coal that are used up immediately and need to be repurchased on a regular basis.

So labor power is entirely fluid capital and the means of production consist of both fixed and fluid capital.

Marx makes the point that Adam Smith and his followers considered the turnover rate of capital to be the fundamental determining factor in categorizing capital, whereas Marx considered the composition of capital—i.e. the distinction between constant and variable capital—to be fundamental. This point is not fully developed here, but one can infer based on various remarks in the text, as to what he’s pointing to. At the end of the chapter on Smith, Marx writes, “Because Adam Smith fixed in this way upon the characteristic of circulating capital as the decisive one for capital value laid out on labour-power… he managed to make it impossible for his successors to perceive that the part of capital laid out on labour-power was variable capital.” (292) So Smith missed the key point that the only portion of capital that is productive of value is labor power. But this is not only a misunderstanding of economics; it hides the exploitation of the worker, the dirty little secret of capitalist production, and in this way contributes a foundational intellectual justification to bourgeois ideology.

In the footnote on the same page he quotes Smith as follows: “‘Not only his’ (the farmer’s) ‘labouring servants, but his labouring cattle, are productive labourers.’” (292) Smith’s misconception becomes the basis for centuries of bourgeois economics that places workers—the source of all value—on the same level as cattle. Indeed, this is why the discipline has been so successful under the capitalist system: it dehumanizes workers in order to better exploit them.